Last year, a 14-year-old boy named Minirdis (mihn-ER-diss) took a road trip across the U.S. But instead of admiring the view, he rode in a box in the back of a truck. That’s because Minirdis is no ordinary boy. He’s a mummy!

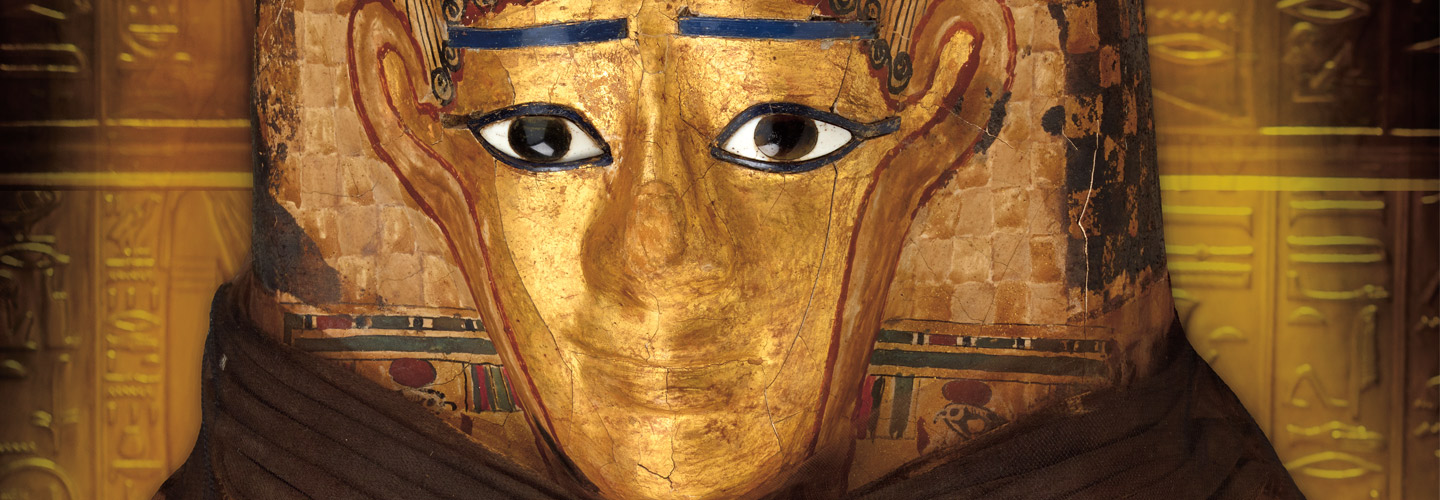

Minirdis was the son of a priest who lived 2,500 years ago in Egypt. When the boy died, his body was mummified, or preserved and wrapped in cloth (see How to Make a Mummy). Then it was placed in a decorated coffin and buried along the Nile River, where it was discovered in the late 1800s.

The mummy of a 14-year-old boy took a road trip across the U.S. last year. His name was Minirdis (mihn-ER-diss). He lived 2,500 years ago in Egypt.

Minirdis was the son of a priest. When the boy died, his body was mummified. It was preserved and wrapped in cloth (see How to Make a Mummy). Then his mummy was placed in a decorated coffin and buried along the Nile River. It was discovered in the late 1800s.